By Maria Ignas (BA 25)

Dr. César Soto regrets he’ll never read all the books he would like to in his lifetime.

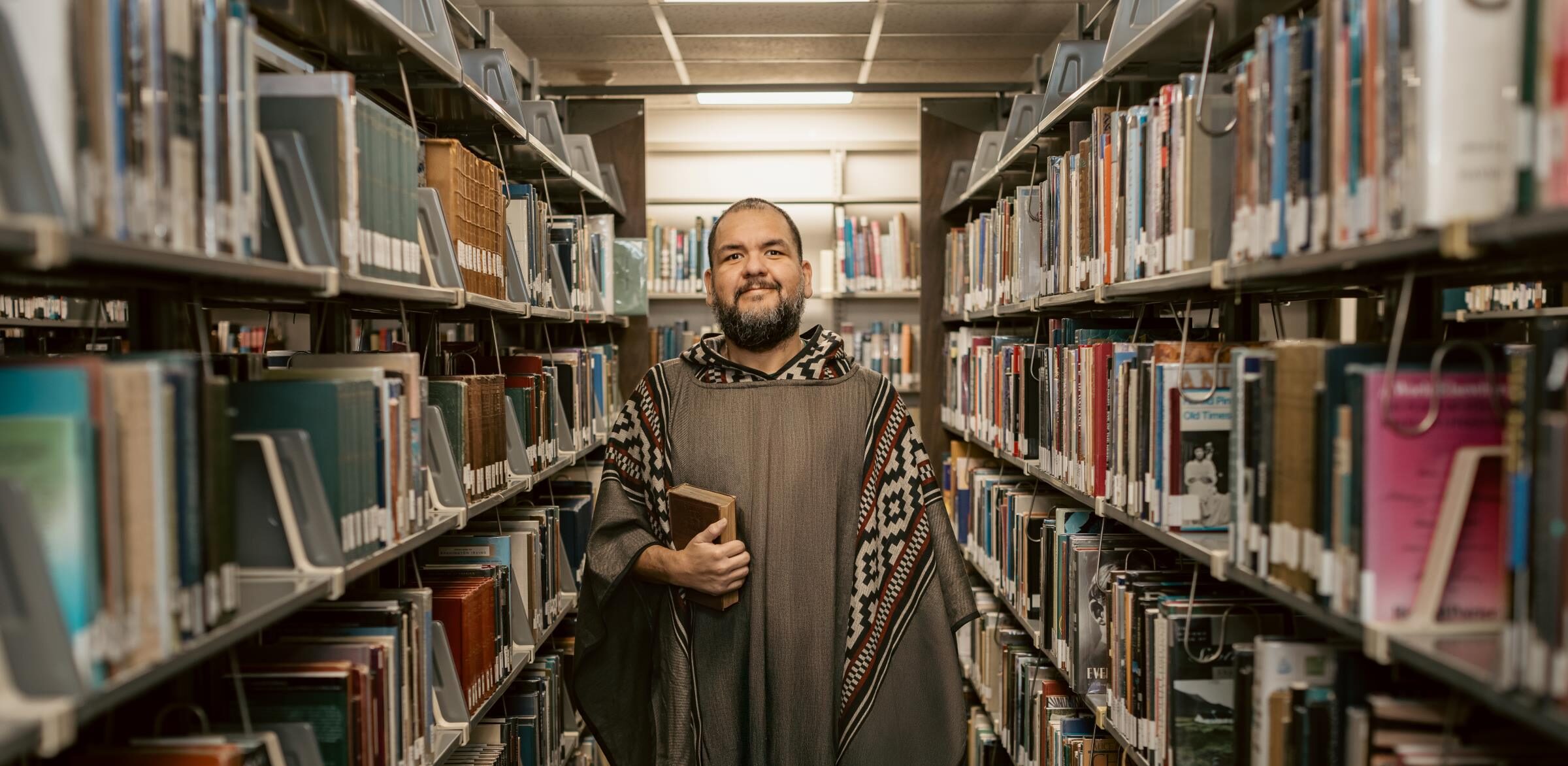

Assistant professor of world literature at Grace College, he has built a career on studying and teaching the best prose the globe has to offer. A teacher at heart, he punctuates every conversation with, “Not to make this a teachable moment, but…” He brings at least three books wherever he goes, and never the same ones day-to-day.

Any major in English will tell you that a good story is universal. Soto’s is no exception.

The Biggest Legacy

Soto was born to immigrant parents in San Fernando, California, also known as “The Valley.” He was raised in Mexican immigrant Pentecostal culture, a vibrant community characterized by storefront churches and coffee-visit hospitality. The entire community regularly rallied around a person or family in need.

In Soto’s part of The Valley, street evangelism trumped intellectual pursuit. Though never impoverished, working-class concerns and piety mattered a whole lot more than, say, applying cultural theory to 19th-century British literature. For Soto, that would come later.

As an academic, Soto deals in theory and abstraction. But his childhood forged his faith through first-hand experience of God’s power. Soto witnessed God’s power reach even his immigrant, working class community through unexplainable healings and the miraculous provision of resources.

Soto’s mother converted to Christianity when he was 3, and she took Christ’s charge to serve the poor as marching orders. She regularly brought Soto and his siblings while she ministered to people facing homelessness and addiction, often offering their home as a haven.

As Soto watched the unlikeliest of people encounter Christ through her, he learned to hope for every soul, no matter how marred by sin it appeared.

“The biggest legacy my mother gave me is introducing me to Christ,” said Soto. “Besides that, she showed me no life is beyond redemption.”

The faith of Soto’s mother saturated her parenting. She only allowed him to consume Christian media, though that didn’t stop him from reading Stephen King along with A.W. Tozer, or Anne Rice with C.S. Lewis.

Soto’s third-grade teacher, Mrs. Wallander, encouraged the voracious reader. According to Soto, her support launched his intellectual development.

He progressed from commercial fiction to literary fiction when he discovered the elevated prose of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights as a 17-year-old. He realized the literature that stretched his mind was the same kind that whispered to his heart.

Undergraduate Success

After graduating high school, Soto enrolled at California State University Northridge. After trying fields in STEM, he semi-reluctantly switched one final time to a double major in English literature and Mexican-American studies.

Soto’s mentors immediately perceived his gifts in writing, research, and literary analysis, so much so they invited him to speak at graduate-level conferences as an undergraduate. He recalls the faculty’s pride when he, a minority student and major in English, won the English Department’s “Honors Thesis of the Year” award.

Moments of God’s power followed Soto even into academics. Moments before presenting his research at his first conference, Soto spotted a scholar whom he had cited sitting in the audience. With a pounding heart and trembling hands, he offered a desperate prayer to God.

“I said, ‘God, just use me,’” said Soto. “From that day on, even the way I moved my hands while speaking changed. My presentation went very smoothly, and they invited me back the next year.”

Soto graduated with his bachelor’s in English in 2007. Keeping his major in English, he earned his master’s degree at the same university five years later, garnering more recognition and academic accolades. A doctorate program was the natural next step for the blooming scholar.

Now What?

A two-time winner of the prestigious Ford Fellowship, Soto was accepted into seven doctoral programs. He enrolled at Notre Dame in 2012 and embarked on his doctorate in English literature.

By now, Soto was tasting the fruits of his intellectual gifts. He was in the midst of his dissertation at one of the most prestigious universities, being mentored by some of the brightest minds. He founded the Latino Graduate Association at Notre Dame (LGAND) – still running 11 years after its inception – and even traveled to Ireland, England, Rome, and Argentina for his studies and archival research.

But spiritually, he was “backsliding.” Living according to his own desires, he had drifted from church attendance, prayer, and discipleship, though seeing God work in his childhood preserved his faith from complete erosion. The tension between his mind and his soul weighed on him, and soon enough, he routinely dealt artificial smiles and empty laughs.

“I was very unhappy but would fake being joyful,” said Soto. “I felt this loneliness.”

He remembers one night in particular, when, sitting on his porch, he wrestled with his unshakable emptiness.

“I thought, ‘I just went to a great conference,’” said Soto. “‘I’m here at Notre Dame. They gave me all this money to study.’ But something inside me said, ‘Now what, though?’”